Ethiopia’s ‘Homegrown’ Economic Reform: An Afterthought

It was within a few months of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD)’s administration coming into office that a radical economic reform program was launched. The government announced their decision to privatize key public enterprises, including Ethio telecom, Ethiopian Airlines and other public utilities.

The urgency with which the authorities got into the business of economic reform brings to mind a scene from the classic play, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, where young Alice asked a Cheshire Cat for directions:

Alice: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?

The Cheshire Cat: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to!

Alice: I don’t much care where!

The Cheshire Cat: Then it doesn’t much matter which way you go!

The parallel with Alice’s story is not limited to a confused sense of direction but also the reliance on strangers for direction. In wonderland Ethiopia too, the authorities have relied heavily on an army of foreign advisors, including the multilateral agencies as well as those not so traceable global influencers who got indirectly involved through frantic shuttle diplomacy, perhaps applying pressure on the authorities to move the economic reform agenda in a direction favoring certain vested interest groups. This culminated with narrowly framing Ethiopia’s economic reform essentially as privatization.

About a year after the launch of the privatization scheme, the government has recently been engaged in a publicity stunt to convince the general public that the economic reform agenda was homegrown and that it was rooted in an Addis Abeba Consensus.

I argue that there is no credible evidence to suggest that the economic reform agenda was truly homegrown. For starters, there is no traceable background study. Economic reforms must be preceded by a thorough diagnosis of the health of the economy, as well as identifying structural bottlenecks and macro-sectoral imbalances.

The findings from expert analysis would be supplemented with institutional analysis often conducted through public participation. A summary of these two would be compiled in a series of non-technical policy papers, or white papers, that policymakers would use as an evidence base to design a suitable economic reform program.

Expert analysis and the evidence base would only generate a menu of options. The authorities are still supposed to set priorities and then implement the reform package, starting from an item near the top of the list.

It is essential to recognize that economic policy is all about setting appropriate priorities. Implementing policies without setting a priority list amounts to a policy blunder. Similarly, implementing the right sets of policies in the wrong order is no better than not having priorities at all.

There was an untenable claim that Ethiopia’s “reform agenda relies on broader diagnostic analyses, beyond the decomposition of growth into the contributions of the factors of production.”

This was posed in the context of responding to earlier criticism regarding miss-specification of economic growth accounting. In my view, we are very far from indulging in the niceties of model specification, which is a luxury in these circumstances. As far as I am aware, there was no background study conducted to generate evidence to inform the decision to formulate Ethiopia’s recent economic reform program, “broader diagnostic analysis” or otherwise.

The only relevant document that comes close to a background study was a report completed in 2018 by the World Bank, The Inescapable Manufacturing Services Nexus: Exploring the Potential of Distribution Services. Evidently though, this is foreign grown. There was no other documented evidence than a power-point presentation displaying details of growth accounting and other relevant facts and figures and posted on the website of the Office of the Prime Minister recently when the Agenda was publicized. However, power-point presentation is not a way to present broad diagnostic analysis on such a major economic policy.

The World Bank report was one of those routine sectoral reviews. It focused on service and distributive sectors and identified some bottlenecks in those sectors. It was claimed inefficiencies in those sectors stood in the way of Ethiopia’s ambition to industrialize. A key recommendation from that report was that “[c]onsidering the weak regulatory enforcement capability of the Ethiopian government, the report suggests using nonstrategic sectors, such as distribution services, as a good entry point into a more comprehensive services reform strategy that is linked with national development plans.”

It seems that the authorities got hold of that recommendation and targeted privatizations of the very sectors that the study covered. Critically, the recommendations in the World Bank study were nothing more than suggestions to reform the distributive services. Privatization was never presented as a compelling policy imperative. Reforming those sectors may mean other broader initiatives such as undertaking far-reaching rationalization and modernizing their management.

Apparently, the phrase “Addis Ababa Consensus” was coined to dissociate Ethiopia’s current reform agenda from the Washington Consensus. The latter was associated with a process by which multilateral agencies dictated structural adjustment programs in developing countries back in the 1980s

However, we have no credible evidence to indicate that Ethiopia’s economic reform emerged from an Addis Consensus, as the authorities would like us to believe. On the contrary, the evidence we have implies that Ethiopia’s economic reform does not even qualify to be called a full-fledged Washington Consensus. At least in the latter there is an element of transparency and rigor reflected in background studies.

Another line of evidence against the term “homegrown” is to examine the timeline in the economic reform agenda. It was only about a month ago that we began to hear about it, when it was mentioned as a topic of a planned event in early September 2019. It was unclear why the government bothered to call for a discussion forum several months after they had already launched a far-reaching economic reform program. What was the point?

After all, major decisions had already been made.

Since the launch of the Agenda, protests have been mounting regarding lack of transparency and public consultation. Apparently, the government was somehow yielding to public pressure and then started what looked like a consultation process, except that those who organized this event might not have realized what they were doing was clearly an afterthought: public participation coming at the end rather than the beginning of the decision-making process!

The very mention of “homegrown” begs more questions: Why “homegrown” in the first place? Where else was an economic reform program supposed to grow?

By belatedly framing the ongoing reform as homegrown, the government is inadvertently admitting that they had so far been implementing a foreign grown reform agenda.

Invoking “homegrown” so late is somewhat akin to what is called a Freudian slip: mistakenly and unintentionally revealing a feeling in the subconscious. This is a forced error caused by the public protests mainly through social media that citizens would need to be consulted, the government should not rely exclusively upon advice from multilateral agencies, foreign consultants and other vested interest groups.

In another piece, “Ethio Telecom: Its Privatization Buzz,” I have discussed a rather baffling situation regarding the extent of involvement by foreign consultants. What is so unique about it?

To begin with, almost all global giants in the world of management consultancy have been involved: Ernst & Young, Deloitte, PriceWaterhouseCoopers and the Mackenzie Consulting Group. The first three belong to those famously referred to as “the Big Four Accounting Firms”.

These firms are so big that their combined revenue in 2018 is nearly twice Ethiopia’s GDP. Clearly, this was like hitting a pin with a sledgehammer. Knowing that the arrangement would come as a surprise to many, the arrival of the giants was accompanied by the publicity that their fees would be paid by the World Bank and other donors.

This was a sort of disclaimer that the big businesses were not out there to further impoverish the already poor Ethiopia. This proviso has not reduced anyone’s curiosity. Why has the privatization of Ethiopia’s public assets become such a magnet? Why so much generosity by multilateral and bilateral donors to pay for the expensive consultancy fees?

One needs to consider the global setting in which Ethiopia’s public enterprises are being privatized. There has been a glut of capital in the hands of big investors. Since the financial crisis of 2008, depositing funds with banks attracted near-zero interest rates.

For that reason, investors have been scanning the horizon to seek opportunities for better yields. Wherever any opportunity presented itself, big investors do quickly land pretty much like a vulture on the scene of a dead animal.

For much of the last two decades, the EPRDF government was fending off pressure from global business to privatize public assets, doing the right thing but for the wrong reasons: public assets were preserved to serve party-affiliated crony businesses.

The Big Four are better placed in terms of networking with potential buyers. Hence, the arrival of the giant firms did not happen by accident. Their mission could as well be a double-edged sword, perhaps primarily serving the interests of potential buyers of those assets.

But why have the authorities plunged straight into privatization in the first place? Why has the economic reform agenda been shrouded with secrecy with little public participation? Why didn’t they bother to consolidate some evidence for their decision-making?

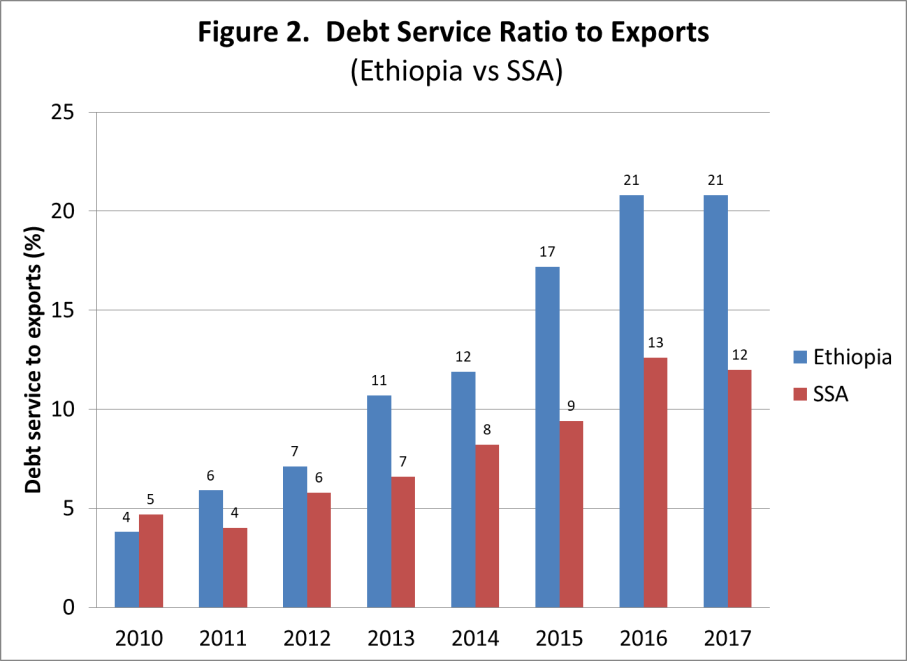

A combination of actors can explain the lack of transparency: the wrong belief that foreign exchange is the most critical economic bottleneck, the pressure from global influencers, and the deals happening behind closed doors with interest groups who would be keen to lay their hands on Ethiopia’s public assets.

The answers to the last two questions most certainly lie in the fallacy of composition, which characterizes the administration’s viewpoint on the health of the Ethiopian economy: insisting on the economic success story narrative but at the same time reporting horror stories about the economic fundamentals at all levels. Crucially, the success story hinged on one economic indicator, the GDP growth rate.

Ethiopia’s economic accounting is in such utter disrepair that Ethiopia’s GDP has been given an existence separate from the country’s economic fundamentals: sectoral, regional and micro-foundations. Either the authorities are not aware, or they do not want to know about the existence of this fallacy. In any event, they have always preferred to show a brave face.

This means they confine the scope of economic reform to mere ownership patterns and imbalances in the foreign sectors. If their view on the health of the economy is right, then the only thing we are left to debate with would be how to go about privatization. Privatization can be optimized to attract hard currency without full surrender of ownership.

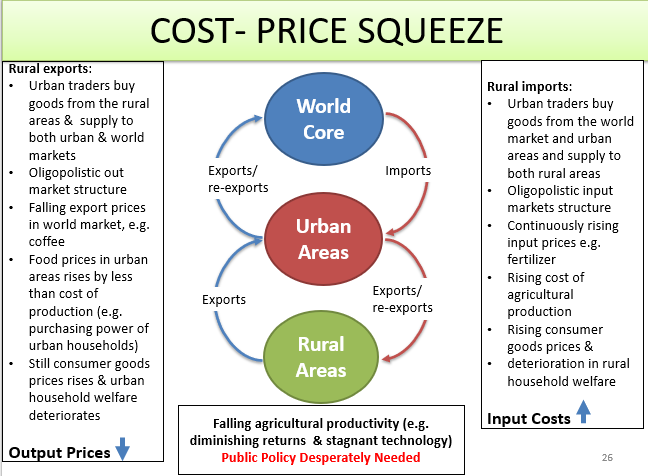

But if the economic success story has no real foundation, then we must go back to square one to rethink and design a more in-depth economic reform program that would address severe imbalances in the domestic economy.

Originally published Oct 12, 2019, Addis Fortune, [VOL 20 , NO 1015], https://addisfortune.com/ethiopias-homegrown-economic-reform-an-afterthought/