Tax Can be a Double-Edged Sword

Ms. Adanech Abeebee, Ethiopia’s Minister of Revenues, is perhaps the busiest among PM Abiy’s cabinet members. Ethiopian authorities seem to be determined to strengthen domestic resource mobilization by improving tax collection and administration efficiency. The renewed emphasis on domestic resource mobilization and self-reliance in public finance can have far reaching implications.

“Tax payer”

Throughout Ethiopian history, there has never been a social contract between citizens and their governments. Regardless, citizens have been paying taxes because they must. In any society taxes are essentially involuntary obligations but they are more so in the context of autocratic governance. The on-going reform in Ethiopia is opening up an opportunity for democratic governance, a realistic change for citizens to enter into social contract with a government they would elect in the near future. Importantly, the transition to democracy is being facilitated by a the reformist government, the most popular leaders Ethiopia has ever had in its history.

In that context, the “tax-payer” principle, a system by which citizens elect, that is to say “employ” a group of citizens as politicians and give them opportunity to specialize in the job of governance. The opportunity to politicians come with the responsibility to become accountable to their electorate about performances in their jobs. The notion of tax payer also encapsulates duties and responsibilities among citizens.

In my opinion, by far the most important benefit of self-reliance in public finance through domestic tax is the fact that politicians would become accountable to citizens rather than foreign governments, NGOs and multilateral agencies. This is a familiar story in the context of Ethiopia, where governments tended to listen to foreign actors and the international community who pay their salaries. It is understandable if they have often ignored opinions of poor citizens. In that context, it is to the best interest of Ethiopia’s citizens to pay taxes to their government so that they can also hold the authorities to account regarding things that might go wrong during their tenure.

The renewed effort to improve tax collection and administration efficiency in Ethiopia should be seen in this broader context. The authorities should be aware that as much as they have the right and the power to collect taxes, they also have the responsibility to efficiently utilize them in delivery of public services. Similarly, citizens should be aware that they cannot expect delivery of public services without paying their fair shares into the tax system. After all, citizens have paid in their lives and livelihood to bring about change in governance.

If citizens want things not to slide back to the bad old ways, then there is no other alternative than strengthening the government they support. The massive popular support Ethiopia’s reformist leaders have garnered provides ample opportunities to experiment with the notion of tax-payer, thereby laying the groundwork for solid democratic governance, even before elections take place.

Caveats

Having said all these, I have to confess I have some caveats, implicit in the heading of this piece. We are experimenting with a new system, introducing a durable notion of tax payer for the first time, and hence we need to proceed with some caution.

First, tax collection administration efficiency is largely determined by clarity in formulating the tax policy, that is the target tax instruments, and administrative capacity to implement it at grass root level. I have reasons to doubt about existence of such a capacity, hence I am very seriously concerned. For instance, what happened in the middle of Oromo Protest makes me seriously doubt that the capacity and awareness of people who administer and collect taxes at local levels. I recall there was utter confusion how to apply rates. There was some haphazard assessment undertaken in a few days. Traders were being asked to pay taxes on their daily sales. At the time, it sounded as if the tax collectors were applying the rates to total sales, rather than the margins, sales revenues less costs of merchandize as well as other running fixed and variable costs including labor and rents of premises, etc. It was utter chaos. By now I hope that mess is cleared and some capacity building has been undertaken at all levels. This matters a great deal. This kind of malpractice can easily erode confidence and weaken the tax-payer principle and hence stifle our fledgling democratic governance.

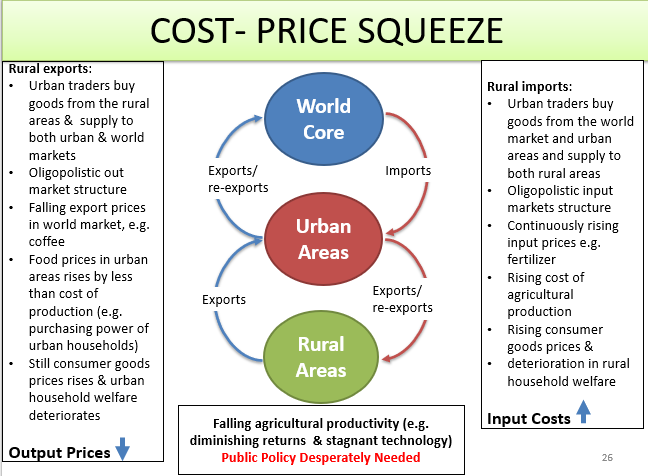

Second, there are studies mostly undertaken by multilateral agencies indicating that Ethiopia has one of the lowest tax to GDP ratio in Sub-Saharan Africa. The conclusion from such studies should not be taken too seriously. The reason is that they start from a questionable premise that Ethiopia has been growing very rapidly in recent decades, the so-called double digit growth. What if the GDP has not expanded to the extent implied in official statistics? It is highly likely that Ethiopia’s GDP has not been growing by as much as indicated by government statistics which has been propagated throughout global databases. For instance, there is credible and solid evidence (a survey by IFPRI and sponsored by EU) that Ethiopia’s agricultural output has been inflated by somewhere between 30% to 40%. If the authorities base their assessments based on official statistics, disregarding such credible evidence, then they would end up levying unfair taxes on households and businesses, eroding their confidence in the tax system.

Third, I have been pondering to write this piece for a little while but I was prompted to act on it today after watching OBN regarding at an event organized on the topic tax collection. Among the things I observed, I would like to raise three interrelated points. It was stated that tax revenue collected in Oromiya increased from birr 600 million to 16 billion during the last decade, a 27-fold increase! This increment can partly be explained by the fact that tax collection and administration has improved significantly during the period. That improvement may explain only part of the story, say half of the increment, that is a 13 times increase. How do we explain the other half, the remaining 13 times increment? Surely, Oromiya’s GDP has not increased grown 13 fold (or 1200%) in ten years. This can be true only if we accept that Oromiya’s GDP was growing in double digit during the period. My hunch it that there must have been some excessive tax burden levied on households and businesses. This is not just unfair, but it would have immense damage on the goodwill between the government and resident households and businesses. Critically, it was also mentioned at the event that about half of the tax collected was payroll tax from public servants in Oromiya. Actually, this is not good news. It means the Oromiya’s public administration has rather been bloated, grown excessively, and tax collected would only get recycled to pay for salary of public servants, leaving much less for capital expenditure and other essential public services.

What is the way out of this conundrum?

From my remarks in the earlier paragraphs, it is clear that I am enthusiastic about the move to strengthen domestic resource mobilization. The caveats I discuss here is to suggest a mechanism by which a sound basis for tax collection would be put in place. That solid basis has got to do with production of material wealth. I would like other ministers in PM Cabinet to be as busy and frantic as Aadee Adanech. Spending too much energy on tax administration amounts to putting too much weight on wealth distribution rather than wealth creation. But logic dictates that wealth has to be created before it is distributed.

In this regard, I have to admit I am not impressed by performances so far of neither PM Abiy at federal level nor that of President Lemma in Oromiya. I understand there has been so many other issues demanding the attention of these reformist leaders. All I am saying is that there are ministers and government departments that have not accomplished anything visible. They need to be nudged and awakened to do their job. A recent half yearly review of Oromiya’s budget performance should be taken as a wake up call.

For instance, I am keen to see ministers of agriculture doing visible nationwide development programs like natural resource regeneration, afforestation of Ethiopia’s exposed landscapes. It is high time that the governor of National Bank of Ethiopia being more busy than Aadee Adanech, engaging in a concerted nationwide effort to expand credit facilities to farmers and small businesses to boost business start ups and job creation. These activities would end up expanding the tax bases. Expansions in economic activities would generate more income that would be taxed.